1.4. Java Unit Testing¶

1.4.1. Objectives¶

Upon completion of this module, students will be able to:

Review the basics of a java class including fields, constructors, methods, parameters, and use of the keyword this

Review debugging code and code coverage

Implement variations for JUnit assert statements

1.4.2. Interactive: Introduction to Hokie Class¶

In this discussion we will be revisiting good testing practices with an example class called “Hokie Class”.

Follow Along, Practice and Explore

- Download to run and explore the java file (see below) from the video on your own in eclipse. You may download the standalone *.java file for this example. To run the standalone *.java file you will need to

create a new Eclipse project, then

create a package within the project called “example” (the package named at the top of the class MUST match the package the file is placed in within the Eclipse project), and finally

download and import the standalone *.java file(s) to the created package.

Hokie.java

1.4.3. Checkpoint 1¶

1.4.4. Intro to Hokie Class JUnit Testing¶

1.4.4.1. A Note about Assert Statements¶

So far in the course when we want to test that a piece of code acted the way we wanted, we’d run a statement like:

assertThat(<something we want to check>).isEqualTo(<expected value>);

This is a more modern style that’s intended to be more readable. However, there is a different form of syntax you can use to create assertions:

assertEquals(<expected value>, <something we want to check>);

This second kind of assert statement is more commonly used today, but it can be tricky to use correctly. When using assertEquals, it can be easy to put the value we want to check first and the expected value second.

For example, say we wanted to check that a variable x was equal to 5.

int x = 4;

assertEquals(x, 5);

Writing like this would be syntactically correct, but potentially confusing because the failure message would read “Expected [4] but got [5]”. In reality, we were expecting 5 but got 4.

Videos in the second half of the course will be using this second, more commonly used syntax. You can continue to use either version. Below, is a table of assertions in both styles. Remember both the isEqualto() and assertEquals() methods use the equals method for the object parameters, be sure to understand how the corresponding equals method works for the objects being compared.

Task |

AssertThat Style |

Traditional Style |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

Checking that |

|

|

While the new style has a |

Check that a double |

|

|

|

Checking that |

|

|

|

Checking that |

|

|

|

Checking that |

|

|

|

Checking that |

|

|

|

Checking two object variables refer to the same space in memory |

|

|

1.4.5. Interactive: Hokie Class JUnit Testing¶

Follow Along and Engage

Download the slides corresponding to the video. Take notes on them as you watch the video, practice drawing diagrams yourself!

JavaUnitTesting.pdf

1.4.6. Checkpoint 2¶

1.4.7. Review of Writing JUnit Tests with student.TestCase¶

1.4.7.1. Use JUnit¶

To make a JUnit test class in eclipse:

Right-click the class you’re creating a test class for in the Package Explorer

Click: New > Class (creating a JUnit Test Case isn’t CS2-Support compliant)

Name the class Test. (i.e. HokieTest, ArrayBagTest)

Click finish (You may want to check the box for ‘generate comments’ if you wish)

Add an import statement: import student.TestCase

Add that your class extends TestCase.

Project Build Path should be configured to have CS2-Support project included (note that CS2-Support needs to be open to appear as an option)

Declare instance variables

Create at least one field of the object of the class you are testing.

Write setUp method

Use the setUp() method to initialize your object(s), it will be run before each test method.

Write test methods for each method in class being tested

Create at least one test method for each of the methods in your class. Each method in your test class needs to start with ‘test’ or else it will not run correctly! (i.e. testGetName, testAdd) For a test method, call the corresponding method on the object and use assertion statements to test your code.

Write additional test methods as needed. A simplified test class example for the Student class:

public class StudentTest extends student.TestCase

{

private Student janeDoe;

public void setUp()

{

janeDoe = new Student(“Jane Doe”);

}

public void testGetName()

{

assertEquals(“Jane Doe”, janeDoe.getName());

}

}

1.4.7.2. Run a JUnit Test¶

To run a JUnit test class:

Right-click the test class in the Package Explorer

Click: Run as > JUnit Test A JUnit window should pop-up and display green if all of your tests are correct and red if one more has failed.

1.4.7.3. Naming Conventions¶

For classes: Add Test to the end of the class name

example: HelloWorld is the class; HelloWorldTest is the test class

For methods: start the test method with test

example: foo is the method; testFoo is the test method

1.4.7.4. Instance Variables¶

Use instance variables to hold values for testing

AKA field variables, member variables

scope of instance variable is all instance methods so variable can be used in multiple tests

in the example above, janeDoe` is an instance variable

1.4.7.5. setUp Method¶

The setUp() method runs before each test method.

Use this method to initialize instance variables

Must be called setUp – remember to make that U uppercase!

1.4.7.6. Code coverage¶

Write tests that test average cases

example: In a list, test for adding to the middle

Write tests that test edge cases

example: In a list, test for adding at the beginning of a list

1.4.7.7. N simple conditions, N+1 branches and tests¶

Assertions in a test method need to make it to every condition of an if-else statement. It isn’t enough that the test reaches the ‘else’ condition. To test an if-else statement properly, the body of each condition must be run during testing.

if (x == 0 && y ==1) // 2 conditions, 3 checks- TF, FT, TT

if (x == 0 || y == 1) // 2 conditions, 3 checks- TF, FT, FF

Clarification for edge and average cases- For a list that contains 100 values, you must check for indices -1, 0, 99, 100, and something in between.

Example: say we had the following:

if ( score >= 90 )

{

System.out.println( “Your grade is an A”);

}

else if ( score >= 80 )

{

System.out.println( “Your grade is a B”);

}

else if ( score >= 70 )

{

System.out.println( “Your grade is a C”);

}

else if ( score >= 60 )

{

System.out.println( “Your grade is a D”);

}

else

{

System.out.println( “Your grade is an F”);

}

Your test class would have to test for all 5 of the above possibilities in order to execute every single line of code in the block of if-else statements.

Sometimes the best way to test your code is to clean your code first!

Cleaning up your code before you test it can save lots of time. In addition, the way you structure your code may make it easier to test correctly.

Example: Say we had written the following inside of a method:

if ( A > B )

{

if ( C != 0 && ( A > B ))

{

// do something

}

}

We can easily clean up this if statement by noticing that we are evaluating A > B twice when it’s unnecessary. We can re-write it as the following:

if ( A > B )

{

if ( C != 0)

{

// do something

}

}

We might decide to un-nest them as well:

if ( (A > B) && ( C != 0) )

{

//do something

}

Now, it’s easier to see all the conditions that need to be tested.

1.4.7.8. Simplify Testing¶

When testing a method with multiple if-else statements, it can usually simplify testing to split each possibility into its own test method.This can be particularly helpful when making sure you’re reaching every condition in a more complex if-else statement block ( a common Web-CAT error ).

Say we are testing a method with the following if-else statement in it:

if ( A > B)

{

//do something

}

else

{

//do something else

}

It might be a good idea to have one test method evaluate this if statement when A > B is true and another test method evaluate the same if statement when A > B is false.

1.4.7.9. Checkpoint 3¶

1.4.7.10. Testing Exceptions¶

If you throw them, then catch them in your testing!

Use a try-catch block in your testing to check if your code has thrown the right exception. In your try block, you should call the method that results in an exception being thrown. The catch block should catch the exception thrown. Then assert that the exception exists, is the correct exception, and (if applicable) contains the correct message.

Example: Say you are trying to access an element in a data structure that cannot be accessed by using an iterator object, so you are testing to check if a NoSuchElementException is thrown with the message “There are no more elements left to iterate over.”. The following inside of a test method will determine if you caught the right exception correctly:

Example:

Exception thrown = null;

try

{

//call the method that should throw a NoSuchElementException

iterate.next();

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

//”Catch” and store the exception

thrown = exception;

}

//assert that an exception was thrown

assertNotNull(thrown);

//assert that the correct exception was thrown

assertTrue(thrown instanceof NoSuchElementException);

//Check the message of the exception is correct

assertEquals(thrown.getMessage(), "There are no more elements left to iterate over.");

1.4.7.11. Checkpoint 4¶

1.4.7.12. Testing toArray() methods¶

The toArray() method returns an Object array containing each element found in a given collection.

Testing the toArray() method requires that we confirm that the actual array of Objects returned by the method matches an expected array of Objects.

Note that the assertEquals and assertTrue methods do NOT provide a mechanism to readily compare two arrays because arrays do not have an equals method defined. We CANNOT simply perform the following:

Object[] expectedArray = {"A","B","C","D"};

Object[] actualArray = {"A","B","C","D"};

assertEquals(expectedArray, actualArray);

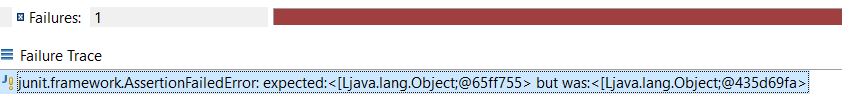

Using the assert in this manner would result in a failed test and an AssertionFailedError (see image below).

nor can we use:

assertTrue( expectedArray.equals( actualArray) );

We need therefore need an alternative option.

One approach is to iterate through the elements of each array, comparing each element in one array with the corresponding element in the other array. If any pair do not match then we can conclude that the two arrays are not equal and therefore return false. Note that we must check ALL of the elements of an array against their counterparts before we can determine if they are equal or not. They will only be equal if we did not encounter any two pairs that were not equal to each other. In this case, for example, we would start by comparing the elements at index 0, i.e. compare expectedArray[0] against actualArray[0],then index 1, i.e. compare expectedArray[1] against actualArray[1], and so on until completed.

Consider using the for loop to help with such a task.

1.4.7.13. Checkpoint 5¶

1.4.7.14. General JUnit Testing Tips¶

Debugging a broken test can be tedious, especially in bigger projects. To make the process easier on yourself, Make sure each test case covers exactly 1 logical component. For instance let’s consider this abbreviated form of our Hokie class:

public class Hokie {

private String pid;

private String hometown;

private int graduationYear;

private int DOBYear;

public boolean setDOBYear(int year) {

if (year > 0 && (year < 3000)) {

DOBYear = year;

return true;

}

return false;

}

public String toString() {

return pid;

}

}

We could create a test case like this:

public void test1(){

// Tests setDOBYear

assertTrue(elena.setDOBYear(1968));

assertEquals(1968,elena.getDOBYear());

assertFalse(john.setDOBYear(12031995));

// tests toString

Hokie gobbler = new Hokie("gobbledee",1973);

assertEquals("gobbledee",gobbler.toString());

}

public void test1(){

// Tests setDOBYear

assertTrue(elena.setDOBYear(1968));

assertEquals(1968,elena.getDOBYear());

assertFalse(john.setDOBYear(12031995));

// tests toString

Hokie gobbler = new Hokie("gobbledee",1973);

assertEquals("gobbledee",gobbler.toString());

}

However if test1 fails, to debug it you now must consider a potential error in the test or a potential error in the setDOBYear() method or in the getDOBYear() method or in the toString() method. Eclipse will direct you to the line that failed but that may not always tell you where the problem actually started! Either way, it’s good practice to write a test method for 1 and only 1 logical component of your code. Dividing these two into separate tests will make debugging easier down the road.

In bigger programs, it may not be enough to make 1 test per method either. Consider the following code:

public int foo(int x, int y){

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++){

x+=i;

if (x % 3 == 0){

x++;

}

y *= i;

}

if (x % 2 == 0){

return x;

}else if (y % 2 == 0){

return y;

}

return 0;

}

You may find it easier to write one test case that handles the logic inside the for loop and a separate test case for the conditionals outside of it. That way if one fails, you know exactly where in your code to look!