4.4. Software Development Processes¶

4.4.1. Software Development Processes¶

A software development process is simply the division of a software project into distinct stages or phases of work. Each stage is characterized by specific activities which are used to help plan and manage progress. A software development process is implemented to improve quality, cost or schedule performance, or all of these things. While there are as many software development processes as there are software practitioners, a few have gained notoriety. These more commonly encountered processes are the ones discussed in this section.

All software development processes are essentially variations on the Plan-Do-Check-Act first described by Francis Bacon in 1620 [Bacon]. Yes, that’s right. There are many software development processes, describing the Plan-Do-Check-Act loop in varying levels of detail. Today, most of these processes are lumped into either of two very broad categories: Agile or Plan Driven.

Plan Driven processes emerged in the 1960’s. As the size of software projects grew, several worrying trends emerged:

Software projects routinely went over budget, or failed to deliver anything

Major defects and failures became more common

Software maintenance costs began increasing

At the time, there was no professional class of programmers. Engineers, mathematicians, and physicists wrote programs to support their work. The first software development processes were adapted from manufacturing and engineering processes. Among the earliest was the systems development life cycle (SDLC). The goals of the SDLC were “to pursue the development of information systems in a very deliberate, structured and methodical way, requiring each stage of the life cycle from inception of the idea to delivery of the final system, to be carried out rigidly and sequentially” [1]. Plan-driven methods continue to be the ‘traditional’ way most software continues to be developed today.

Agile methods grew out frustration with the rigidity of the plan-driven processes commonly used in the 1990’s just as the tech boom was heating up. Technology was changing faster than projects could keep up and many projects failed because by the time they were ready to deliver, the playing field had changed enough to make the product, if not obsolete, at least a less compelling commercial success.

The practitioners of Agile methods tend to be a diverse and fractious group, but have, as a group, drafted a single statement that nearly all agile process models embrace. It is known as the Agile Manifesto [2]. Here it is in it’s entirety:

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.Through this work we have come to value:Individuals and interactions over processes and toolsWorking software over comprehensive documentationCustomer collaboration over contract negotiationResponding to change over following a planThat is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

Much of the documentation available today implies that choosing a process is an either - or proposition. That a project must be either plan driven or agile. The reality is a bit more nuanced and there can can be bitter disagreements between proponents of different process models. One way to summarize the differences between the two groups is to examine the myths propagated about them.

Common misunderstandings directed at Plan-driven processes include:

- Can’t respond to change

Too big and complex

Products cost more

Only for large organizations

Old-Fashioned

Universally Applicable - Software development is uncertain and the X process improves predictability therefore all software developers should use process X

Common misunderstandings directed at agile processes include:

Agile is synonymous with Hacking

- It’s a ‘silver bullet’

Easy to implement, Very effective

- Do whatever you want

No cost or schedule commitments

- Incompatible with traditional processes

No Documentation, Architecture, or Planning

Not appropriate for Firm Fixed Price Projects

- Universally Applicable

The pace of IT change is accelerating and Agile methods adapt to change better than disciplined methods therefore Agile methods will take over the IT world.

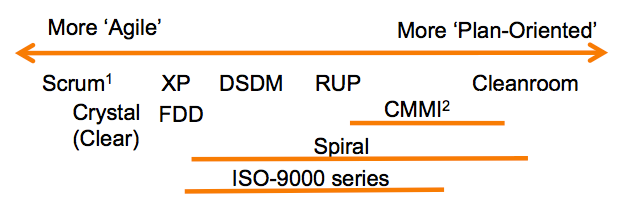

The truth is that many agile and plan-driven methods exist. All are more or less plan-driven and some have more ‘agile’ characteristics than others. Therefore, a more accurate characterisation is to think of processes existing along a continuum, with the axis representing the relative amount of willingness to embrace change (agility) at one and the importance of comprehensive up front planning and adhering to that plan at the opposite end. No process exists at either extreme.

Scrum is not a complete software development process description as it covers only project management.

CMMI is a process improvement model, not a software development methodology, but is often considered one.

Each group has a sweet-spot where it outperforms the other as the following table summarizes.

Characteristics |

Agile |

Plan Driven |

|---|---|---|

Primary Goals |

Rapid Value, respond to change |

Predictability, stability, & high assurance |

Size |

Small Teams and projects |

Large teams and projects |

Environment |

Turbulent, project-focused |

Stable, organization-focused |

Requirements |

Stories. Rapid change expected. |

Formal Specs for projects, capability, interfaces, quality & similar. Gradual change expected. |

Development |

Simple design, short increments. Refactoring assumed inexpensive. |

Detailed architecture and design. Refactoring assumed expensive. |

Test |

Executable tests validate requirements |

Documented test plans validate requirements |

Balancing the trade-offs between agility and discipline is a decision each software development project has to make on their own.

Figure 4.4.2: Adapted from Balancing Agility and Discipline: A Guide for the Perplexed [Boehm03]¶

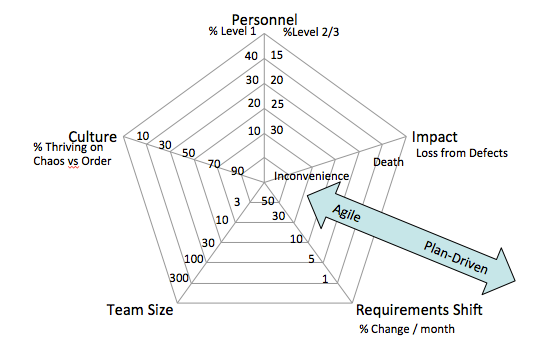

4.4.1.1. Waterfall Method¶

Initially described in 1970, the Waterfall process was another early software development process adapted from manufacturing and construction processes. The waterfall model is a sequential design process, in which progress is seen as flowing steadily downwards (like a waterfall) through several distinct phases.

While many variations exist, most waterfall processes in use go through at least the following phases:

Requirements: System and software requirements, captured in a product requirements document.

Analysis: resulting in models, schema, and business rules

Design: resulting in the software architecture

Implementation: the development and integration of software

Verification: the systematic discovery and debugging of defects

Maintenance: the installation, migration, support, and maintenance of complete systems

The waterfall model was simple to understand and was widely used throughout the 1980’s, but came under criticism primarily for it’s lack of flexibility. Although officially endorsed by the US Department of Defense in 1985, the DoD supplanted it with other process guidance ten years later.

Peter Kemp / Paul Smith, Waterfall model (Adapted from Paul Smith’s work at wikipedia) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

4.4.1.2. Rational Unified Process¶

The Unified Software Development Process or Unified Process is a popular iterative and incremental software development process framework. The best-known and extensively documented refinement of the Unified Process is the Rational Unified Process (RUP). Other examples are OpenUP and Agile Unified Process.

The Rational Unified Process (RUP) was created by the Rational Software Corporation in 1996. RUP is not a single concrete prescriptive process, but rather an adaptable process framework, intended to be tailored by the development organizations and software project teams that will select the elements of the process that are appropriate for their needs.

RUP is based on a set of building blocks and content elements, describing what is to be produced, the necessary skills required and the step-by-step explanation describing how specific development goals are to be achieved. The main building blocks, or content elements, are the following:

- Roles (who)

A role defines a set of related skills, competencies and responsibilities.

- Work products (what)

A work product represents something resulting from a task, including all the documents and models produced while working through the process.

- Tasks (how)

A task describes a unit of work assigned to a Role that provides a meaningful result.

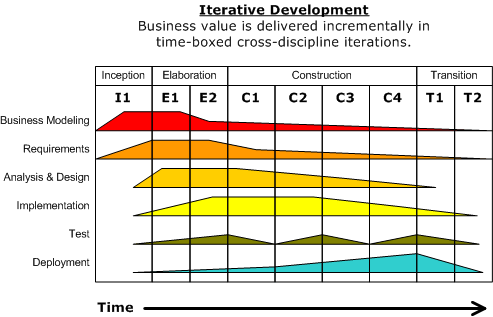

Figure 4.4.4: RUP disciplines and iterations¶

The RUP defines a project as a series of iterations. An iteration is a period of time in which project tasks are performed. Within each iteration, the tasks are categorized into nine disciplines:

Six “engineering” disciplines

Business modelling

Requirements

Analysis and design

Implementation

Test

Deployment

And three “supporting” disciplines

Configuration and change management

Project management

Environment

4.4.1.3. Other Plan-Driven Approaches¶

- Military Methods (DoD)

- DoD-STD-2167

A document-driven approach that specified a large number of “Data Item Descriptions” for deliverables. Tailoring was encouraged, but infrequently done.

- MIL-STD-1521

details a set of sequential reviews and audits required.

- MIL-STD-498

revised 2167 to allow more flexibility in systems engineering, planning, development, and integration.

- MIL-STD-499B

defines the contents of a systems engineering management plan.

- General Process Standards (ISO, EIA, IEEE)

- EIA/IEEE J-STD-016

a generalization of MIL-STD-498 to include commercial software processes.

- ISO 9000

a quality management standard that includes software.

- ISO 12207 and 15504

address the software life cycle and ways to appraise software processes.

- Cleanroom (Harlan Mills, IBM)

Uses statistical process control and mathematically based verification to develop software with certified reliability.

The name comes from physical clean rooms that prevent defects in precision electronics.

- Capability Maturity Model for Software (SEI, Air Force, others)

A process improvement framework, SW-CMM grew out of the need for the Air Force to select qualified software system developers.

Collects best practices into Key Practice Areas that are organized into five levels of increasing process maturity.

- Software Factories (Hitachi, GE, others)

A long-term, integrated effort to improve software quality, software reuse, and software development productivity.

Highly process-driven, emphasizing early defect reduction.

- CMM Integration (SEI, DoD, NDIA, others)

CMMI was established to integrate software and systems engineering CMMs, and improve or extend the CMM concept to other disciplines.

Its a suite of models and appraisal methods that address a variety of disciplines using a common architecture, vocabulary, and a core of process areas.

- Personal Software Process (PSP)/Team Software Process (TSP) (Watts Humphrey, SEI)

- PSP

A structured framework of forms, guidelines, and procedures for developing software. Directed toward the use of self-measurement to improve individual programming skills.

- TSP

Builds on PSP and supports the development of industrial-strength software through the use of team planning and control.

4.4.1.4. eXtreme Programming (XP)¶

Established in the late 1990’s by Kent Beck, XP is regarded as perhaps the most famous agile method. XP was certainly among the first to gain attention from mainstream software development projects. XP was refined from experience gained developing an information system for Daimler Chrysler corporation. As agile practices go, it is quite proscriptive, fairly rigorous and initially expects all practices to be followed. Kent Beck has been quoted as saying

If you’re not performing all 12 practices, then you’re not doing XP.

In Extreme Programming Explained, Kent Beck describes extreme programming as a software development discipline that organizes people to produce higher quality software more productively. XP attempts to reduce the cost of changes in requirements by having multiple short development cycles, rather than a long one. Rather than a burden, changes are considered a natural, inescapable and desirable aspect of software projects, and should be planned for, instead of attempting to define a stable set of requirements.

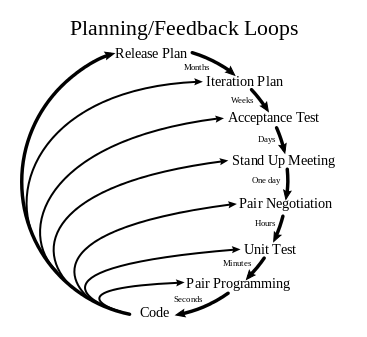

Figure 4.4.5: Planning and feedback loops in extreme programming. [4]¶

XP is characterised by several core practices including stories, pair programming, simple design, test first, unit tests, and continuous integration.

The XP process describes four basic activities that are performed within the software development process: coding, testing, listening, and designing.

- Coding

XP argues that the only truly important product of the software development process is code – software instructions that a computer can interpret. Without code, there is no working product.

Coding can also be used to figure out the most suitable solution. Coding can also help to communicate thoughts about programming problems. Programmers dealing with a complex programming problem, or finding it hard to explain the solution to fellow programmers, might code it in a simplified manner and use the code to demonstrate what they mean. Code, say the proponents of this position, is always clear and concise and cannot be interpreted in more than one way. Other programmers can give feedback on this code by also coding their thoughts.

- Testing

Unit tests determine whether a given feature works as intended. A programmer writes as many automated tests as they can think of that might “break” the code; if all tests run successfully, then the coding is complete. Every piece of code that is written is tested before moving on to the next feature.

Acceptance tests verify that the requirements as understood by the programmers satisfy the customer’s actual requirements.

System-wide integration testing was encouraged, initially, as a daily end-of-day activity, for early detection of incompatible interfaces, to reconnect before the separate sections diverged widely from coherent functionality.

- Listening

Programmers must listen to what the customers need the system to do, what “business logic” is needed. They must understand these needs well enough to give the customer feedback about the technical aspects of how the problem might be solved, or cannot be solved. Communication between the customer and programmer is further addressed in the planning game.

- Designing

As software systems grow, the importance of design increases. Small programs can be constructed with comparatively little design, however as software size grows, the more design is required. Often more upfront design is required as well as checking and revisiting designs throughout the lifetime of the project.

Don Wells, Planning / Feedback Loops (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:XP-feedback.gif) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

4.4.1.5. Crystal¶

Established in the late 1990’s by Alistair Cockburn, Crystal is conceived as a family of software development processes organized by color, clear, yellow, orange, red. To date, only Crystal Clear, the most light-weight in the family, has been completely documented.

Crystal provides different levels of “ceremony” depending on the size of the team and the criticality of the project. Crystal practices draw from agile and plan-driven methods as well as psychology and organizational development research.

4.4.1.6. Scrum¶

Scrum is an agile software management process. That is, it describes how software development teams should be organised and lets each team determine what technical software development activities they should perform.

Projects are divided into 30-day work intervals (“sprints”) in which a specific number of requirements from a prioritized list (“backlog”) are implemented. Short (10-15 minute) “Scrum meetings”, held daily, maintain coordination within the team and with project stakeholders (pigs and chickens).

4.4.1.7. Feature-Driven Development (FDD)¶

FDD is a lightweight, architecturally based process that initially establishes an overall object architecture and features list. Projects then proceed to design-by-feature and build-by-feature activities. Both design-by-feature and build-by-feature are incremental software construction methodologies. In FDD, the use of UML or other object-oriented design methods is strongly implied, if not explicitly required.